Part 3 in a series of reflections.

Building on Foucault's work, David Halperin contributes to the exploration of sexuality as a discursive formation in two of his books.

Building on Foucault's work, David Halperin contributes to the exploration of sexuality as a discursive formation in two of his books.

One Hundred Years of Homosexuality deals not with the Greeks who are its historical subject, but rather the rise of the discourse of sexuality itself. In this work, Halperin explores the Greek pederasty more fully than Foucault did in his History of Sexuality, Vol. 2.

For the Greek citizen, sex with a boy was one form of sex among many. He might have sex with his wife, or with a prostitute, or with his servant (either male or female), or with a young male for whom he provides patronage. In each case the object of his sexual advances does not bestow upon him any certain identity.

In modern categories of sexuality, we might be prone to call this citizen bisexual, yet the term is not a precise fit. This is because in each case, the citizen must perform in the active role, penetrating his sexual partner. Further, only males of certain social classes (ward, servant) may be objects of his affection.

It was generally considered distasteful to continue to have sex with a pubescent boy once he began to grow a beard. Further, while there was, generally speaking, no shame involved in being the passive partner in a pederastic relationship while a male was still young, submission as a penetrated partner would deprive a man of his status as a citizen once he was older.

Further, as Foucault had previously pointed out, the passive youth was expected to submit out of a sense of obligation and social decorum. However, there shouldn't be any hint that he enjoyed being the object of penetration. Such nuances trouble the standard categories of sexuality in modern discourse.

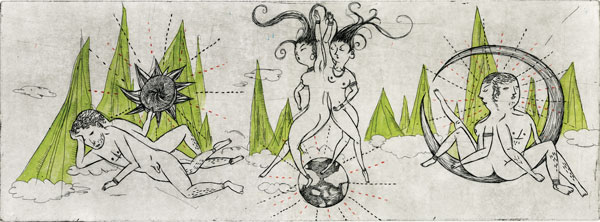

In his own work, Halperin also points to the comical creation narrative recounted by Aristophanes in Plato's Symposium. The first humans, Aristophanes tells us, were round like the gods (planets) that had created them. They possessed two heads, four arms, four legs, and two sets of genitals. There were double males, double females, and androgynes who possessed both a penis and a vagina.

Symposium, by Plato. Art/adaptation by Yeji Yun. From The Graphic Canon, Volume 1 (Seven Stories Press).

When the humans attempted an insurrection against the gods, Zeus struck them down. However, as their worship and veneration was needed, it was not possible to kill them all. So Zeus divided each human into two halves.

Subsequently the humans searched around for their other halves, and when they found them, embraced each other in an attempt to become whole again. Zeus eventually moved their genitals around to their front sides so that the halves of the androgynes might through sexual intercourse give birth to more human beings.

In the telling of his story, Aristophanes makes an interesting note. While the double women are barely mentioned at all and the androgynes are the male-female couplings that continue the species, the double-male humans are given a separate commentary. These noble creatures, Aristophanes tells us, give rise to youths who search for older men and the older men who search out the youths for erotic relationships.

Unlike the other two types of humans, Plato's account clearly points out the age difference (and societal ranking) of the partners involved in this relationship. There is no room here for two grown men of equal stature to enter into a sexual relationship–the hallmark of the modern category of homosexuality.

In his How to Do the History of Homosexuality, Halperin further explores categories of (primarily) male sexuality of the Greco-Roman period that do not easily align with modern conceptions of homosexuality.

Effeminacy

Halperin first deals with models of effeminacy that do not have analogs within our own time. The Greek term malakos (Latin mollis) or "soft" describes the category of men who are given to excesses of sexual pleasure. As such they become dandies, availing themselves to stylish clothing and face powders to make themselves more attractive to the objects of their affection, both male and female. They were often described as soft in body as well, giving up the firmness associated with masculinity.

Included also in the category of effeminacy is the Greek kinaidos (Latin cinaedus) who is also given over to sexual desires. The kinaidos seeks out sexual gratification in a host of ways, allowing himself to be penetrated by another male or by a woman with a phallic object in his quest for further pleasures.

However, his sexual encounters are not exclusively same-sexed. His primary objective is to experience further forms of sexual gratification, so in addition to becoming objectified through penetration, the kinaidos still plays the active role with both men and women.

Halperin notes that modern readings often confuse the kinaidos with homosexuals; however, their sexual tastes defy the logic of this category.

Pederasty

Expanding on his earlier work, Halperin introduces pederasty as his second category. He emphasizes that unlike modern categories of sexuality, a particular age and social standing is prescribed for each of the partners, the eromenos (beloved) and the erastes (the lover). Further, the eromenos is normally expected, once he is grown, to abandon relations with grown men and to assume his role as a citizen. He will take on a wife and be head of household. While he may engage in active sexual penetration of youths, he will also have sex with women.

Friendship

Third, Halperin explores the category of friendship, which in a homosocial setting has certain overtones of homosexuality. However, friendship differs in that the deep bonds of affection do not necessitate consummation of a sexual relationship.

Many epic tales from the Greco-Roman period explore deeply affectionate relationships that, under the suspicious eye of modern discourses of sexuality, would be read as homosexual rather than simply homosocial.

Inversion

Finally, Halperin explores the category of inversion. Here, the ancients saw a woman trapped in a man's body. According to this logic, the quest for sex with men was not homosexual because the psyche of the invert is actually female.

The Shaky Ground of Modern Sexualities

Halperin suggests that modern discourses of homosexuality are clouded and destabilized because they are built (consciously or not) on earlier categories. This problematizes easy questions of desire for members of one's own (perceived) sex or the opposite and renders the categories somewhat unstable.

Discussions of sexuality are further complicated by work around questions of essentialism and construction of gender and sex. Up to now, we have assumed that there are easy working definitions for man and woman or male and female, but the work of a second set of theorists has had the effect of disrupting assumptions here as well.

I'm glad I stumbled onto your blog. This is another fascinating post. I like Halpern's account of the meaning of μαλακοὶ and wonder what references he has for this view. It would be nice to think that such a meaning is intended in 1 Corinthians 6:9.