In Being Human, a course on theological anthropology, I had to present some observations on the second half of Ian McFarland's Difference & Identity: A Theological Anthropology[1] and lead a class discussion. What follows is the written presentation and the questions I used to start the class discussion.

In last week's reading we finished on a chapter exploring our encounters with others through Jesus. Using the parable of the Good Samaritan as an interpretive framework, McFarland suggested that Jesus was able to help his disciples and others with whom he interacted to see beyond labels to the persons addressed by God.

In last week's reading we finished on a chapter exploring our encounters with others through Jesus. Using the parable of the Good Samaritan as an interpretive framework, McFarland suggested that Jesus was able to help his disciples and others with whom he interacted to see beyond labels to the persons addressed by God.

However, Jesus is no longer a human presence with us as he was in first-century Palestine. What's more, the quest for the historical Jesus is complicated by both a scarcity of source texts and our own tendency to see in the texts we have a Jesus that looks like us.

Biblical narratives of Jesus' life and ministry are first marked by the needs/agendas of the communities that created them. They are further subject to our own "twisting" to make them fit to our presuppositions (85). Because Christ now sits at the right hand of the Father, McFarland suggests that we encounter Jesus indirectly through the Holy Spirit, in the Sacraments, the testimony of the Church, and through encounter with others outside of the Church.

Unlike the Son, who was incarnate in the person of Jesus, the Holy Spirit does not have a physical body. Instead, it works "through the flesh-and-blood existence of human beings" whenever our neighbors bear testimony to the risen Christ (87). This includes the proclamation of the word during worship services, but is also interpreted more broadly to be any sharing of the risen Christ in the testimony of our neighbors.

The proclamation of the Word and the practice of the Sacrament both have as their subject the narrative of Jesus' own life; however, they take place within the community of the church. Baptism is a mark of an individual relationship with Christ, but it is celebrated within the larger community of human beings who are also called to personhood by Christ. Likewise, the Eucharist (or communion) is characterized by its corporate nature.

However, McFarland is quick to point out the presumption involved in assuming that Christ can only be encountered within the church or by its members. One of the primary functions of the church is evangelization, or the spreading of the good news (as opposed to making clones of a particular Christian culture). As such, people outside of the church experience the call of Christ through interaction with Christians who, rather than holing up in their own community, bear witness to the world of the presence of Christ. The only way this is possible is for the church to point away from itself and to Jesus (92).

However, McFarland is quick to point out the presumption involved in assuming that Christ can only be encountered within the church or by its members. One of the primary functions of the church is evangelization, or the spreading of the good news (as opposed to making clones of a particular Christian culture). As such, people outside of the church experience the call of Christ through interaction with Christians who, rather than holing up in their own community, bear witness to the world of the presence of Christ. The only way this is possible is for the church to point away from itself and to Jesus (92).

McFarland suggests that the gospel message can be summarized in the declaration that Christ has addressed all of humanity as persons, yet in order for those within the church to understand what this means, it is necessary to remain in relationship with those outside of the church. The meaning of personhood is progressively revealed as more and more individuals are incorporated into the body. The only way to the church continues to learn what it means to be a person is to continue the spread of the gospel, coming into contact with more and more persons Christ has addressed.

In addition to learning the definition of personhood through continued contact with the world, McFarland suggests that encounters with non-Christian "others" allow opportunities for Christians to encounter Christ in ways that they will not inside of the church, remembering that Jesus has a preferential option for those on the outside (95). It is in recognition that our neighbors are called by Christ as persons that we continue to grow in our own understand of exactly what personhood encompasses.

Human Relationships and Reciprocity

In the next chapter McFarland focuses on the question of how we can take difference seriously without introducing hierarchy into our thinking. He begins by pointing out that human identity as it is formulated in Christ establishes an equality that breaks down many of our traditional categories.

Using passages that refer to baptism into Christ (1 Corinthians 12:13; Galatians 3:26-28) we find the lack of distinction between Jews and Gentiles, slave and free, and male and female. While the first two distinctions are of less importance in contemporary Christian discourse, discussions around gender and hierarchical roles remain a hot topic within the church today and will be explored in more detail below.

In addition to these three different areas of division, McFarland adds those who are marginalized due to sickness (the woman with the hemorrhage), occupation, status as sinners, confessional identity and ethnicity. He notes that Jesus' responses to various forms of marginalization are not all the same. Those who were sick he healed, while he forgave sinners. These two categories in particular appear to hinder the full expression of the personhood of the individual.

But Jesus' response to each of the other categories did not involve transforming the marginalizing characteristic into something else. (For example, though he healed the woman with the hemorrhage, he did not also make her a man.) Instead, Jesus showed a preferential treatment for those whose full personhood was threatened by their marginal position within hierarchical structures.

While the original problems of cultural identity, ethnicity and slavery that bubbled up in early church controversies have been largely resolved in the modern Christian context, the issue of male/female hierarchical dualism and scriptural references to wives submitting to their husbands continue to be problematic in the contemporary church. McFarland focuses on Ephesians 5:21-33 as an example of the ongoing tensions in this area.

Following modern biblical criticism, he places the text historically between two other benchmark texts: 1 Corinthians 11:2-16 and 1 Timothy 2:9-15,[2] noting that the Ephesians text is the only one of the three to present a fully developed argument for gender hierarchy with an appeal to christology.

Briefly, the writer of Ephesians begins by exhorting readers to subject themselves to one another. McFarland continues by asserting that the husband is the head of his wife, just as Christ is head of the church.

Just as the church is subject to Christ, so also should a wife be subject in every way to her husband. McFarland notes that the argument presupposes a difference between the husband and wife that renders them uninterchangeable in their roles and incapable of mutual submission.

Just as the church is subject to Christ, so also should a wife be subject in every way to her husband. McFarland notes that the argument presupposes a difference between the husband and wife that renders them uninterchangeable in their roles and incapable of mutual submission.

Thus we have a proof text for the submission of women that appeals to the relationship between Christ and the church for its authority. However, McFarland is not satisfied with this reading.

First, he suggests that all such texts must be read in the larger context of the tradition taken as a whole. Secondly, he undertakes a deconstruction, examining the "theological slippage" inscribed in the text.[3]

McFarland begins his work by noting that the pericope has be improperly framed, suggesting that the proper beginning point of the thought is verse 18. By including the preceding text, submission to one another in Christ (v. 23) is parallel to the preceding exhortation to live a life in the Spirit that includes singing to one another (again mutuality) songs, hymns, and spiritual songs and praises to God (118). Within this larger context, McFarland suggests that the unilateral submission of wives to husbands is awkward.

Further, the analogy breaks down when we compare Christ as head of the church with the husband in the role of a savior who sanctifies his wife (119). The evident comparison in the English translation is also not as clear in the grammar construction of the Greek, which contains two conjunctions that signal a discontinuity in the analogy. Verse 24 begins with ἀλλά (but), while verse 31 further breaks the parallels by introducing the clause with πλήν (however, but, nevertheless).[4]

With this analysis in mind, McFarland concludes that when we acknowledge the lack of parallel between the salvific relation of Christ to the church and a husband to his wife, the evidence of Christ's own ministry as recorded in the gospels would appear to undermine any claim of unilateral submission of women to men based on this passage (121).

By deconstructing the Ephesians passage, McFarland hopes to show that it is not enough to simply privilege one scripture passage over another when constructing a theological argument. For the passage in question, we must be able to explain how rejection of unilateral submission of one to another is compatible with the idea of submission to Jesus as sovereign during certain moments such as teaching, reprimand, and correction. While Jesus' own modeling as the ruler who serves is a central theme of the gospels, there are moments when he (and subsequently, Christian leaders) necessarily assumed a position of authority (superordination) in order to provide proper guidance.

Question

McFarland's deconstruction of the Ephesians text hinges on the breakdown of parallel between the identity of Christ and a human husband, as well as some semantic markers in the Greek text. What do we do if other texts (e.g., 1 Corinthians 11:2-16) do not lend themselves to the same critical analysis?

Personal Difference and Human Nature

During last week's discussion, one of McFarland's starting premises was that theological anthropology has much work to do in dislodging the image of the Western white male as the only viable image of what it means to be human (see chapter 2). In this chapter he takes up the poststructuralist discussion of the function of language and the necessary exclusion of the other that takes place each time we draw a boundary in our discussion (126).

In order to avoid any essentialist criterion in defining personhood, McFarland has suggested that human beings are not persons in and of themselves, but only as a matter of having been addressed by the Word.

But once we have established this part of the argument, we fall back to the same original problem that any discussion of difference appears to include. We appear to be unable to talk about difference in any meaningful way without reference to categories that we often think of as "generic," but in reality are laden with socially-conditioned, implicit, normative values. These norms reinscribe an implicit essentialism that homogenizes the other as part of our discourse.

The full breadth of McFarland's argument is too much to encapsulate within the allowed page limit, but he concludes by borrowing from Eugene Rogers' suggestion that we must hold open our idea of what it means to be a person. Rather than fostering a preconception of what it means to be human, we must remain open to a human nature that will only become clear with the eschaton (142).

This formulation complements the idea from the previous chapter that the church grows in its understanding of personhood as it encounters through its spread of the good news more individuals who have been addressed as persons by the Word.

Symptoms of Being Human

Using the creation narrative of Genesis 1, McFarland concludes by suggesting three symptoms of being human: dominion, sexual difference, and fruitfulness.

Dominion, McFarland notes, carries many negative connotations in our own context, as human beings have used this passage ideologically to justify exploitation of natural resources while inflicting immense ecological damage upon our planet (149). As a corrective to this theological account, dominion is interpreted through the person of Jesus Christ who, rather than lording his divinity, took on the role of a slave. The dominion of Christ then is not tyrannical, but instead is self-giving.

It is through this lens that we are to understand humanity's role as servants. Dominion in the creation story is "a human obligation to the nonhuman" and "an orientation to other creatures who are as much esteemed by God as human beings are" (150).

McFarland further characterizes dominion as the ability to analyze our situation and to manipulate our environment in a manner that goes beyond instinct (151). We will return to this element of his description in my criticisms below.

Sexual difference enters Genesis 1 when Eve is created as a helper and partner to Adam. McFarland suggests that singleness is not a symptom of humanity, as in the narrative God declares that it is not good for Adam to be alone.

While sexual difference is certainly not the exclusive domain of human beings, McFarland suggests that because the Genesis narrative mentions male and female only in relation to humanity that it is reasonable to conclude that sexual differentiation is somehow symptomatic of what it means to be human (153).

Like dominion, sexual difference is understood in its fullness only from a christological perspective – in the metaphor of Christ's relationship to the Church as the bridegroom to the spotless bride (153).

Finally, fruitfulness is characterized primarily by the presence of children within the human community. Viewing this third symptom christologically, McFarland suggests that even though Jesus had no biological children (that we know of), the gospel narratives nonetheless report his emphasis on fostering "the least of these" as a part of his ministry. In this context, fruitfulness is not so much about procreation as it is "about creating an environment in which children are welcomed" (156).

While McFarland attempts to give the reader something more to hold onto while we are waiting for the eschatological revelation of what it means to be a human person, I find the three symptoms presented to be of little practical help. By his own admission, not all human beings express all three symptoms. But moreover, it seems that other animal species express these three symptoms in varying degrees.

For example, there are some higher order primates that are capable of an elementary level of non-instinctive tool usage with the purpose of manipulating their environment.

For example, there are some higher order primates that are capable of an elementary level of non-instinctive tool usage with the purpose of manipulating their environment.

More widespread are sexual differentiation and fruitfulness, which are commonly found in many species. With this in mind, one might make an argument that a bonobo monkey is a person (though not human).

Further, because some human beings may not clearly manifest any of these three symptoms, we are left in the familiar predicament alluded to in discussion of essentialist anthropologies that would deny human personhood based on an absence of required characteristics.

While McFarland doesn't require any of these three symptoms, we are left again with persons of whom we can make no positive statements regarding their personhood.

An exploration of sexual difference also seems appropriate.

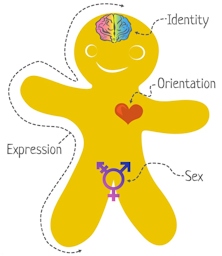

McFarland acknowledges poststructuralist arguments that characterize gender identity as a socially constructed paradigm rather than an essential biological category (126-127). While this admission is certainly welcome, it does little to explore the complications of sexual differentiation that move beyond gender dimorphism assumed in the male/female paradigm presented in Genesis 1. That McFarland asserts in his concluding chapter that it is a "fact" that children are born male and female (157) serves to underscore this point.

Modern science recognizes that sexual differentiation and gender are constructed of many different elements including external genitalia, internal genitalia, hormonal gender, chromosomal gender, social gender and self-perception. In the absence of ambiguous external genitalia we have, for the majority of human history, made deceptively simplistic determinations regarding the nature of male and female.

Modern science recognizes that sexual differentiation and gender are constructed of many different elements including external genitalia, internal genitalia, hormonal gender, chromosomal gender, social gender and self-perception. In the absence of ambiguous external genitalia we have, for the majority of human history, made deceptively simplistic determinations regarding the nature of male and female.

However, within the biological world there are myriad permutations of gender that go beyond our common understandings. Sexual differentiation is not nearly as clear cut as the example of Adam and Eve would suggest.

What's more, intersexed children in our own time are often surgically altered at birth to ensure their conformity to the prevailing gender paradigm. A question arises as to how this field of gender/sexual variation would affect McFarland's point.

Finally, while McFarland discusses the possibility of a definition of fruitfulness that goes beyond biological reproduction, he is quick to refocus specifically on children, relegating mention of philosophy, art, poetry and language to a footnote and citing criticism that such human artifacts move being human into "an undesirably abstract and disembodied view of human being" (157). If human culture is of any value, it appears to be only in fostering children. Further discussion of this point might also be fruitful.

Questions

Is it realistic to ask an ancient creation myth to be the sole bearer of weight in the construction of a modern theological anthropology? Put another way, in light of the worldview of the original authors and the questions they were attempting to answer, how might the creation stories of Genesis inform such our modern enterprise?

McFarland points to the nongenital (and still to be consummated) union between Christ and (his) Bride the Church as the christological significance of sexual differentiation (153). What is the necessity of bracketing out the potential of sexual consummation in the marriage metaphor? And without a consummative component, what is the purpose of the bridegroom/bride metaphor? (Compare with clearly sexual male/female metaphors found in the Old Testament used to describe God's relationship to Israel.)

In chapter 8 McFarland suggests that poststructural criticism "raises the question of whether categories like gender signify anything more than a temporary configuration of human interests" (127). Does the additional information regarding gender/sexuality provided here change the way in which sexual differentiation (and the discussion of progeny) might be viewed in McFarland's project?

[1] McFarland, Ian A. Difference & Identity: A Theological Anthropology. Cleveland, Ohio: Pilgrim Press, 2001.

[2] McFarland notes that the Ephesians text is located "both canonically and, by critical consensus, historically" between the other two texts. While the historical element is relevant, the canonical location is not, seeing as New Testament canonical order is achieved by arranging the epistles by author, from longest to shortest.

[3] Though not explicitly named, McFarland appears to be appealing to Derrida for his hermeneutic.

[4] It is interesting to note that the KJV translates the ἀλλά as "therefore," while the NRSV leaves out the introductory word completely.